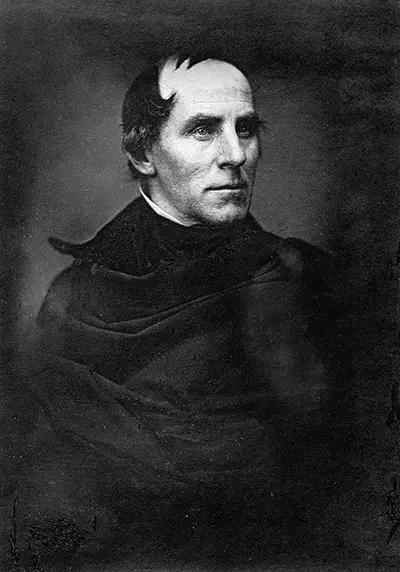

Thomas Cole was an English-born American landscape artist of the mid-19th century. Widely accepted as the founder of the artistic movement known as the Hudson River School, renowned for its stable of talented landscape artists, Cole created many well-beloved classic scenes of 19th century New England.

Born outside of Manchester in 1801 he emigrated with his family to the United States in 1818 and fully adopted it as his home. He lived and worked in New England until his untimely and sudden death from pneumonia in 1848. While landscape painting was well established as an art form in Britain, it was not practiced in the US at that time.

Thomas is credited with bringing landscape art to America and inspiring a new and brilliant generation of painters to explore the joys of the magnificent scenery around them. Some 143 paintings and drawings accredited to Cole exist today and they can be found in many prestigious Museums throughout the United States.

Early Life and Influences

Cole was a largely self-taught artist. He learned his skills mainly from studying artists' works which he admired and reading books. Clearly, he was blessed with raw talent and he was only in his early twenties when he decided that he wanted to make a living as a painter. He began his career as a portrait artist making money on whatever commissions came his way, but it wasn't long before he realised that it was what he saw around him that truly ignited his imagination. Raised in the hectic and polluted Manchester of the industrial revolution, it is small wonder that Cole was truly inspired by the wide open, clean spaces he found in this new and exciting America.

All the inspiration required for Thomas' verdant artistry was to be found in the glorious countryside around him; the clean and vast surroundings were in such juxtaposition to industrial revolution England. In 1829 Thomas returned to England in the hopes of expanding his skills by studying the great landscape artists who exhibited there.

He found great mentors in the titans of the day such as Turner and Lorrain but also John Constable whom Cole met and befriended. Constable's work was a life-long inspiration to Thomas, and he is said to have turned to it again and again for guidance and vision.

It was not only fellow artists who inspired Cole's work. He often found insight for his compositions through popular literature of the time. The Last of the Mohicans (1827) is clearly an image conjured from the pages of the 1826 novel by James Fenimore Cooper of the same name. In addition, perhaps his most famous series of paintings, The Course of Empire was, by his own admission, based on Lord Byron’s poem, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1818).

The Hudson River School

The Hudson River School was an informal movement describing a group of landscape painters who shared the same romantic vision of New England and the surrounding area. Cole is considered the founder of this group because the critic who coined the phrase was describing an exhibit of his paintings. However, Thomas himself never felt affiliated to any school and didn't consider the Hudson River School a movement at all. There were nonetheless a number of famous and extremely talented members of this non-movement, Asher Brown Durand, Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt to name a few.

The common threads that bound these great artists was a deep and abiding appreciation of the New England landscape, particularly that around the Catskills where they lived. They believed that the American landscape was an expression of God and that there was a divine rite in the peaceful coexistence of man and nature. The founding pillars of the movement were three-fold; discovery, exploration and settlement and they sought to express these ideals through romantic, sometimes even idealised portrayal of nature. Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1827-1828) exemplifies the philosophies of the school in that it takes the bible theme and places it in what Cole considered God's country, bringing forward the God in the landscape.

The atmospheric details in the Hudson River School paintings were oftentimes spiritual in their use of colour and light. Their brushstroke techniques led to what was to become the famed luminism style of subsequent American landscape artists. Eventually, after Cole’s death, the scope of the artists expanded into the developing western territories and South America leaving a legacy which chronicled the expansion and European settlement of the Americas.

The Pastoral Landscape

Many of Cole's paintings were of simple scenes, exquisitely captured. In some cases, his subject matter was extremely ordinary, yet it was so finely rendered, he clearly found the grace and helped the viewer see it too. An excellent example of this is one of Thomas' earliest exhibits, Lake with Dead Trees (Catskills) (1825) housed in the Allen Art Museum, Oberlin College, Ohio. This painting depicts a still lake surrounded by dead trees, yet the light coming through the clouds is glorious, elevating the tree to a luminous gold at the same time highlighting the real subject matter, two magnificent deer by the waters' edge. It is an expression of the eternal cycle, a perfect balance of life and death.

Perhaps Cole's best-known pastoral landscape is, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm (1836), more commonly known as The Oxbow. It has become quite an iconic image in American art history. The painting shows us the dichotomy of 19th century American landscape in that to the left of the picture is wild forest with large storm clouds overhead, and they are baring down on the peaceful but cultivated valley below. This work is quintessential in its expression of the principles of the Hudson River School; exploration, discovery and settlement, while at the same time it has a melancholy aspect as the wilderness is on the margins and is retreating. This painting was commission by Thomas' great patron Luman Reed but today it can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Allegorical Works

Cole was a deep-thinking man and his art often demonstrated his inner thoughts on life and the human condition. Over the course of his career he had several occasions when he was allowed to explore his beliefs through his commissions and these works took the form of allegorical series of paintings. The first of such opportunities was in 1833 when Luman Reed funded what was to become Thomas' master work, The Course of Empire (1833-1836).

These five paintings; The Savage State, The Arcadia or Pastoral State, The Consummation of Empire, Destruction and Desolation all chronical the rise and fall of an imaginary city and detail a warning to the governments of the day of hubris and over reaching your grasp in the pursuit of greatness. The series re-examines the theme of cycles, a topic which Cole explored often in his work. It was and is a great triumph of both artistry and storytelling and art historian Earl A. Powell praised it as a truly heroic moment in the history of American painting. Today it is housed in the New-York Historical Society and remains a cautionary tale to us all.

Finally, any review of Thomas' allegorical works must include The Voyage of Life series (1840) which again explore the subject of cycles but this time they depict the four stages of human life. The paintings, Childhood, Youth, Manhood and Old Age tell the story of a traveller on a boat through the American wilderness guided by an angel. These works do not only chronical the ages of man, but also the seasons of the year and the wisdoms to be harvested at each stage in the journey; the man goes from innocence to strength to faith to acceptance. The paintings, commissioned by Samuel Ward were a huge success with both critics and the public, but Thomas' patron would not show them in a gallery, preferring to keep them in his own private collection. Ultimately, Cole was forced to create a second series in 1842. Said to also detail Cole's own path in finding his faith, the paintings were described at his funeral by William Cullen Bryant as "a perfect poem, purely imagined". Today the series can be found in the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

The Legacy of Thomas Cole

Cole, like his contemporaries in The Hudson River School, left a glorious chronical of the beauty of the wilderness before it gave way to industrial change and as such it is part of American heritage. He clearly influenced those who followed him and laid the groundwork for a very proud tradition of landscape artists in America. However, more than that, he opened the door for artists to experience the American dream; an immigrant settler, if you will, who fully embraced his adopted home and found his genius. He laid out a road map of caution to all who would see it that we must appreciate what is in the here-and-now and not blindly move on with progress for progress' sake. It may be too late for much of our wilderness, but it is a lesson we might do well to heed before we miss it all together.