An Italian painter of the Renaissance period, Pietro Perugino was a member of the Umbrian school. His best-known pupil was Raphael, and in his youth he was described by Giovanni Santi as being on a par with Leonardo da Vinci.

He was one of the first Italian painters to use oil paint. Before this, he worked in tempera, the most usual method of the time, where pigments were dissolved in a water-based emulsion, often egg yolk. Tempera was the medium employed for painting frescoes on wood panels, from the twelfth to the fifteenth century, when oils gradually took over. Born Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci in around 1450 near Perugia in Umbria, he took his professional name from the city, it being common practice to identify people by their birthplace. Little is known of his early training, but he was possibly taught by Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, a minor Perugian artist, or in other local workshops. He may also have been a pupil in Arezzo of the great Piero della Francesca, from whom he would have learnt all about geometric orderliness and linear perspective. Working here would have made him an associate of the renowned Luca Signorelli, but in any case, they certainly knew each other, and the influence of the latter's talent as a draftsman can be discerned in the work of Perugino.

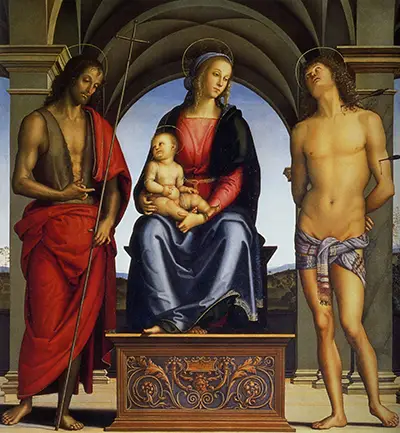

Early commissions included several frescoes for the convent of the Ingessati fathers; unfortunately these works were lost during the siege of Florence. He also provided many cartoons, which the fathers transformed into stained glass. An example of Perugino's tempera work is the tondo (circular picture), The Virgin and Child Enthroned between Saints, now in the Musée du Louvre in Paris. Moving to Florence by the early 1470s, Perugino is thought to have worked for Andrea del Verocchio, where he would have met a promising young apprentice by the name of Leonardo da Vinci, as well as Filippino Lippi, Lorenzo di Credi and Ghirlandaio. Verocchio's teaching is evident in the early work of Perugino, with its tidy lines and its adoption of chiaroscuro techniques. The latter, with its emphasis on contrasting shades to suggest a three dimensional picture, would have fed into the artist's apparent interest in Flemish art and its focus on light. Florence was now his home, with a successful studio, although he may have retained a second one in Perugia.

By 1478 Perugino was in Rome, where he had been commissioned by the papal court to produce frescoes for the Sistine Chapel, along with Ghirlandaio, Rosselli, and Botticelli (another influence on Perugino). His fresco here, Giving of the Keys to St. Peter (1481-82), is considered to be a masterpiece, and was a move towards High Renaissance art. This new movement championed clear composition, a sense of space and perspective, and simplified formality. However, Perugino failed to seize the initiative to develop this further, leaving both da Vinci and Raphael, joined by Michelangelo, to become the giants and innovators of the style. This fresco for the Sistine Chapel incorporates Perugino's self-portrait, together with that of the architect. Unfortunately, others produced for Pope Sixtus IV at the same time didn't survive, with three being destroyed to make way for Michelangelo's Last Judgement. After this, Perugino worked on the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence, and then in 1491 was asked to join the committee planning the completion of the Duomo, as Florence cathedral is known.

At the zenith of his artistic abilities by then, Perugino produced some of his best work in Florence, with central figures framed by Renaissance architecture and open backgrounds, conveying an overall feeling of harmony. His Pietà of 1494-5 for the Uffizi is a perfect example of his mature style. His knowledge of the late fifteenth-century portrait-style of Flanders is obvious in his own portraits, with the finest example being Francesco delle Opere, also dating from the mid-1490s. Perugino especially admired Hans Memling, whose influence is particularly apparent here. In 1496, the artist developed his spacial theme further, when he completed a three-part fresco in Florence's S. Maria Maddelena dei Pazzi. Here, he portrayed space and landscape lacking architectural perspective, and placed figures untidily around the scenes.

In 1500, Perugino returned to Perugia to complete a fresco cycle for the city's guild of bankers, commissioned for their hall, the Sala dell'Udienza, with the humanist Francesco Maturanzio as consultant. It included the vault, for which Perugino provided the design, while his students probably did the painting. In the mid-pilaster of the hall, Perugino positioned his own portrait as a bust. This was probably finished around 1500, going by the date that is recorded opposite the artist's self portrait. Another figure is that of Fortitude. Raphael would have been a pupil of Perugino at that time, learning how to apply frescoes, and this allegorical figure is sometimes attributed to the young assistant. Shortly after this, Perugino became a prior of Perugia. After being accused by Michelangelo of being a bungler, he responded with the marvellous Madonna and Saints for the Certosa of Pavia. Parts of this are now scattered around various museums, including London's National Gallery, with only God the Father with Cherubim still in situ.

Perugino's trademark mild Madonnas and gentle saints with their calm surroundings were somewhat out of fashion by the start of the sixteenth century, and were considered rather dull. In addition, his later work saw a formulaic repetition of earlier subjects, and both of these negative factors contributed to a slide in popularity. His Annunziata altarpiece for the Basilica dell'Annunziata was not a success, and eventually, fed up with criticism from the Florentines, and the loss of students, Perugino left for Umbria in 1505. Three years later, he returned to form in Rome with his painted roundels for the ceiling in the Vatican's Stanza dell'Incendio. However, the artist commissioned to do the frescoes on the walls in the stanza was Raphael, Perugino's past pupil, who was now considered to have developed greater ability than his one-time tutor. It must have been bitter-sweet for the older man to know that he had helped to encourage this talent, only to see himself surpassed eventually.

One of his last works was to finish a commission that had been started, ironically, by Raphael in S.Severo, Perugia. That was in 1521, but he carried on painting until his death from the plague in the winter of 1523. It is believed that his last fresco was Nativity, executed in S Maria Assunta in Fontinagno, where he died. This is close to Perugia, so Perugino lived up to his nickname, having been born, died, and often based in or near the city. This last fresco was transferred to canvas, and is now in the possession of London's Victoria and Albert Museum - an appropriate home, given that his slightly sentimental style and atmospheric compositions are said to have influenced the English Pre-Raphaelite movement of the nineteenth century.

Despite falling from favour in the face of so much artistic energy and innovation, Pietro Perugino remains one of the key artists of the late quattrocentro, having spread classicism through the northern and central regions of what is now Italy. The importance of space and harmony spurred Raphael onwards into the High Renaissance, while his tutor was left behind. It should be remembered, though, that teacher and pupil admired and fed off each other, with Raphael successfully persuading Perugino to adopt a lighter touch.