Luca della Robbia is a famous Italian sculptor who worked right across the 15th century, mainly in the city of Florence. He was considered by some to have been even more talented than the likes of Ghiberti, Donatello, Brunelleschi and Masaccio.

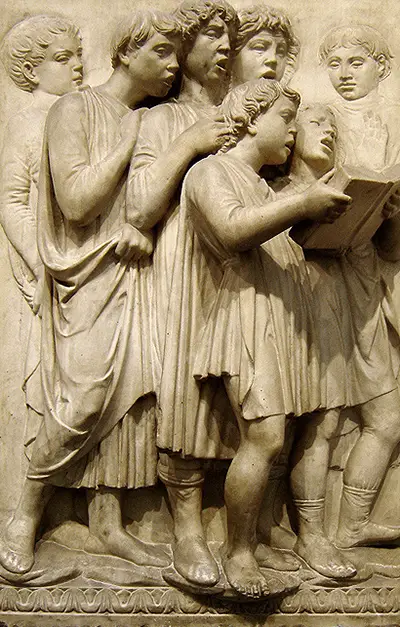

He would produce most of his major commissions with the help of his studio, which included a number of members of his family. His work was predominantly based on religious themes, in keeping with most artists during this period, and his work recorded piece was titled the Cantoria which was to be part of a permanent installation within the Cathedral of Florence. It lasted from 1431-1438 and is a sculptured balcony intended for singing from above all others. He produced some exquisite carved figures on a series of panels for this project, whilst working under the supervision of Brunelleschi at the time. It took so long to complete these panels, that he actually is known to have developed significantly as a sculptor as the commission developed. The figures invariably portray how the completed installation was to be use, with groups of people singing merrily.

One can examine the different panels to see clear comparisons in style, where we can visually see how he becomes more confident and starts to produce more dynamic compositions where figures are less rigidly structured and a greater sense of movement can be felt. Luca della Robbia had clearly shown enormous promise in order to get this commission in the first place, but even in his early thirties he would not have been considered experienced enough at that time in order to be given a free reign on this project. He may have learnt more whilst working on Cantoria that in any of his previous studies, with the process of real work, under the direction of a major artist, being truly rewarding.

The sculptor mixed with some of the finest Italian sculptors in his early days, whilst working as an assistant. All of these experiences would serve him in as he prepared to join the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname, a sort of sculptor's guild in Italy for those who specifically work in stone and wood. He was accepted in 1432 and was now able to start to build further connections within his career which was a crucial element in this period towards developing a strong reputation and then securing more commissions. He now felt able to work as the figurehead on new commissioned projects, and no-longer needed to serve as an understudy to someone else. Besides his time with Brunelleschi across the 1430s, he also helped out with Lorenzo Ghiberti's construction of the North Doors some years earlier.

Giorgio Vasari wrote about this sculptor and claims that he actually trained under Leonardo di Ser Giovanni as a goldsmith, but other accounts dispute this. Vasari revealed some highly significant and intriguing details about Luca della Robbia in his many publications about the regions's famous artists. He claimed, for example, that the reason that he was awarded the commission for the work in the Florence Cathedral was down to involvement from the Medici family, which underlines the kind of support that he was starting to receive, even in the earlier stages of his career. Political issues would often be involved with the awarding of commissions during this time, as it remained within Europe for several centuries, and so it was essential for a favoured sculptor to retain his popularity into the future. The artist's delivery of Cantoria repaid the faith shown in him and also established his name within the major names of Florentine art at that time, with this region being the spearhead of Italy's entire output at that time.

The ambitious Della Robbia then decided to immediately switch his talents to alternative materials, constantly desiring challenge and progression within his career. As stone went out, in came stone and bronze. He completed some decorative elements for the bell tower at Florence Cathedral, increasing his involvement at this venue. Amongst other projects was also his collaboration with Michelozzo for some bronze doors for the Sacristy of the Cathedral. His role here was clearly far more senior than when he worked for Brunelleschi some years earlier and his opinion was now being sought, rather than merely following instructions to the letter, as had previously been the case. This series was considered artistically not as impressive as the ones produced by Ghiberti, but still are impressive artistic pieces.

The artist then started to work with terracotta from the 1440s and would use a technique of tin-glazing that had not been seen before and was entirely his own invention. Sadly, he took many of the technical secrets behind it to his grave, such was his secrecy over certain aspects of his career. It first appeared in his work on the Visitation in the San Giovanni Fuoricivitas Church of Pistoia, and that would then lead to several commissioned pieces for the extraordinary Il Duomo in Florence, perhaps the most significant calling for an artist from this city. The building itself dominates the city's skyline, both physically but also artistically and to be asked to contribute to it would have been a huge thrill for him. His artworks for it were titled Resurrection (1445) and the Ascension of Christ (1446). Luca della Robbia greatily appreciated the way in which the smooth surfaces created through this technical work could perfectly reflect light and colour across a room.

"...I suppose nothing brings the real air of a Tuscan town so vividly to mind as those pieces of pale blue and white earthenware... like fragments of the milky sky itself, fallen into the cool streets, and breaking into the darkened churches..."

Walter Pater, 19th-century writer, describing the signature style of Luca della Robbia with terracotta sculpture

He would continue to keep busy until his death in his early eighties, slowly relying more and more on his assistants as became older. The family members included in his large, but tight-knit studio included nephew Andrea della Robbia plus his great-nephews Giovanni della Robbia and Girolamo della Robbia who joined later on. It is believed that he also passed on some of his technical discoveries to members of his family, but was reticent to pass them on to anyone else. His studio also developed a strong business which varied the quality of their work in order to sell to different markets, where the uniqueness of their moulds would dictate pricing. Luca would have felt more comfortable with putting his reputation and financial future partially into the hands of his extended family, rather than complete strangers. We were many years from concepts such as copyright during the 15th century, making artists far more secretive than they might become centuries later on.

With regards his family, it was Andrea who would play the most significant role in collaborating with Luca. He spent over thirty years helping out until, finally, he was handed the reigns of the whole studio in 1482. Andrea himself had a large family and brought a number of his children into the business as soon as reasonably possible and this ensured the continuation of the Robbia name in art circles into and across the 16th century. There was a development from Luca's initial work where he was mainly focused on his own artistic preferences plus the directions requested by a small number of commissioning clients before his family then started to open up their scope of work in order to draw in all manner of new work. For the first time portrait sculptures, plus still life, landscape, and allegories would appear within their portfolio as the younger generation would start to embrace new ideas within the 16th century.