Creativity is an intrinsic part of being human. While every animal experiences emotions, no other animal has the ability to express how it thinks, feels and sees through the creation of works of art.

Our ability to visualise and create is thousands of years old. It is sobering to remember that the magnificent art of the Palaeolithic, which represents the oldest form of human creativity, has been known for just two centuries.

Until the 1830s, art was considered to be the invention of civilised humans, beginning with the Greeks, falling into barbarism with the Dark Ages at the end of the Roman Empire, and re-emerging with the Renaissance.

The art of earlier civilisations such as ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, even though intriguing and highly developed, was viewed as more primitive than that of Hellenic culture. The Greeks laid the foundations of art as we understand it, or so it was argued. See also the Seven Wonders of the World.

The artefacts of the Palaeolithic were not entirely unknown. People had been finding worked stone arrowheads and spearheads for centuries, often attributing them to the work of supernatural beings such as fairies or speculating that they fell from the sky when there was a thunderstorm.

Then, in 1833, a French physician named François Mayor discovered and made drawings of some engraved and decorated antlers which were attributed immediately to the Celts, since this was a period of great interest in the pre-Roman peoples of western Europe, most of whom were designated "Celtic".

The Shock of the Old

In fact, Mayor had recorded the first examples of Palaeolithic art. Even greater glories were to come with the discoveries of the magnificent paintings of Altamira and Lascaux, which depicted animals such as bison and horses that looked as fresh and vibrant as if they were created days earlier. As the antiquity of these works began to be appreciated, the effect was shocking.

Old beliefs regarding time and space were falling into the abyss; the universe was unimaginably vast, the earth unimaginably old, and humans had been creating art for thousands of years. The oldest cave art, recently discovered, is Indonesian, and dates back over 40,000 years.

Beautiful, mysterious and clearly the work of talented artists, the cave paintings captured the imagination of the public. What was their meaning? Why were they created? After two centuries of research, investigators now believe the European cave paintings, and corresponding early art from all over the world, represent the strivings of the human imagination to comprehend its environment.

They are not static art works; they were probably the focal point of other activities, using fire along with sound and movement to create a collaborative experience that would contribute to a sense of community and magical control over the environment.

The themes of beauty and functionality were therefore established long before the philosophy of William Morris (“Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.”) The art of ancient Egypt, beginning with the uniting of the two lands in 3100 BCE, also seems mysterious and magical, yet was essentially functional.

Egypt was long credited as having been given “nine measures of magic” at the dawn of time, leaving all other cultures only one tenth to share between them. Magic was a vital aspect of existence, permeating every area of life, just as the River Nile brought life-giving black silt to fertilise the ground annually. Heka, the Egyptian word for magical power, provided additional dimensions to the two-dimensional paintings and reliefs on the walls of temples and tombs.

When the tomb-owner and his wife and family were represented as sitting in front of a giant feast, with vessels of wine or beer and fowl and legs of beef stacked high in front of them, it was Heka that restored them to reality in the afterlife. Perspective was less important than showing people, animals and objects in as complete a form as possible.

Therefore if the viewer looks closely, they will see the impossibility yet practicality of Egyptian art; humans have faces that are viewed in profile, yet eyes that are viewed as if from the front; their chests are seen as though from the front and their legs from the side, with both arms visible. What matters is that they should be depicted as holistically as possible.

It was a view that was reflected in the art of the embalmer, who replaced missing fingers, toes, limbs or eyes with various substitutes to make the dead complete again.

Egyptian art was practical. It permitted the dead to enjoy eternity in an afterlife ruled by Osiris, god of the dead, in a land that looked like the real Egypt, but without any pain, labour or deprivation; in other words, a preternaturally real Egypt.

As time passed, more naturalistic themes emerged, creating artworks representing a vision of life in the real Nile valley that still astonish the viewer today. Colourful butterflies and realistically depicted insects settle on plants, fish swim in the cool depths of the river, rulers ride in chariots to war or the hunt, and workers cut the barley in the fields to make bread and beer.

A Selection of Famous Paintings from the History of Art

Semi-Divine Rulers and the Harmony of Heaven and Earth

Egypt in the days of pyramid building was still essentially a stone age culture, ruled by semi-divine kings whose massive monuments have survived to this day. The theme of the ruler who is part divine, part human, continued to develop throughout bronze age Egypt and most of the ancient world.

Many monuments and reliefs were dedicated to the elite as ruling intermediaries between heaven and earth. They were essential to the continuing triumph of order over chaos, an idea that is expressed in the art of many cultures again and again. As time passed, ordinary people began to acquire concepts that were previously only available to the elite, such as the idea of life after death. These themes were reinterpreted in their own tombs.

Until European explorers set out across the oceans and discovered new cultures, views on the nature of art were those of the known world, encompassing the Mediterranean, north Africa, Syria, Anatolia, Persia, and eventually, northern Europe and Scandinavia. However, the magical power of art was not confined to these regions.

From China to the cultures of South America, magical art and artefacts were produced for semi-divine rulers to ensure not only their own existence in the afterlife, but also the continuance of cosmic harmony in the world of the living. Magic, the gods and their relationship with humans were expressed in art and architecture for both the living and the dead.

Images or symbols of supernatural beings are common to the art of all cultures, from the Inuit to aboriginal Australians. Art could function as a literal memorial, a memory system that reminded those who saw it of people, places, journeys and events. Sacred games such as bull leaping on Crete and the ritual ball games of South America have also provided inspiration for art.

The art of pre-colonial north America has its own mythologies and pantheons of divine and semi-divine beings. The massive sculpture of Hindu temples revealed the complex lives of the gods, while tiny statues of household deities, in many cultures representing ancestral figures, protected the families that worshipped them. Until modern times, societies did not compartmentalise art as a separate activity. It was entangled with every other aspect of life and death.

Greek Art and the Human Form

With the rise of Greek culture in the first millennium BCE, the focus turned to more natural expressions of human and divine forms. For the Greeks, the gods were superhuman beings who could be represented as just that – supremely powerful, yet recognisably human.

What remains of many ancient cultures today, particularly statuary, does not give a true indication the original impact of the art. Statues were brightly painted. Art was a vibrant experience, elevating the natural to supernatural. It was a vital part of communication between this world and other realms. Art was the language of the gods.

In later times in Egypt, when there was much Greek, and subsequently Roman, settlement, hybrid forms of art combining Greco-Roman and Egyptian elements developed. The most famous examples are the Fayum portraits, haunting encaustic works of art that were used to cover the faces of mummies.

They gaze from the wrappings, realistic images of people painted in the prime of life who now remind the observer of its brevity. We owe our scant knowledge of some of the beliefs of the Scythians to talented Greek goldsmiths, who created works specifically for the Scythian market north of the Black Sea.

These remarkable pieces, now in collections in Ukraine and Russia, show the clothing and horses of the Scythians and hint at their religious and magical beliefs. Where cultures meet, there has always been syncretism, the uniting of different beliefs and deities. The same was true for art.

Imperial Art and Architecture

Imperial art was the hallmark of the Roman period, with the emphasis on the power and authority of emperors, many of whom were also generals. They were still depicted as semi-divine beings in the statuary that was erected in the inner sanctuaries of their temples from Britain to Egypt and beyond.

The wealth and multi-cultural nature of the empire also meant that artists had the opportunity to experiment. Domestic settings had their own forms of art which included statuary, mosaics and practical items such as pottery. Thanks to the preservation of cities such as Pompeii and Herculaneum after the calamitous eruption of Vesuvius, wall paintings revealing both the sacred and the secular in Roman life can still be seen.

Yet various art forms had flourished for centuries in Europe and north Africa before the arrival of Roman rule. We know less about these people because they were not literate societies. However, they speak to us through their art, telling the observer of their talents in metalworking and enamel, creating beautiful and functional items for everyday use from horse harness decoration to buckets and weaponry.

Styles that predate the Romans continued long after the end of Empire, to change once more as they came under new influences. The swirls and spirals of ancient European art underlie the rich symbolism of Celtic Christianity.

Religion and Art

All religions, whether the mainstream religions of the world or local belief systems, make use of some form of art to express meaning and belief. Only fundamentalism denies the creative in religion. Depictions of the natural world, or formalised and geometric representations of natural forms as in Islamic art, can reveal aspects of the nature of God to the believer.

The Abrahamic religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, have provided inspiration for much of the world’s art. Yet so too have personal beliefs, represented in the art of household shrines from Africa to the Americas. The nature of the religion reflects the nature of its art.

Western European art has been heavily influenced by Christianity, with both the western and eastern Roman empires, Rome and Byzantium, being the original storehouses. The movement of Christianity across Europe can be mapped through the art and artefacts of each region, from the Lindisfarne Gospels to images of the Three Kings at Cologne.

Early medieval times, once known as the Dark Ages, were far from dark. In the ancient centres of the world such as Cairo, art and architecture still flourished, while in Ireland the Celtic Church produced glorious art that reveals a level of skill that is hard to match even today.

The Renaissance: the Enthroning of Art

The Renaissance is often seen as representing not only the restoration of the principles of the art of classical antiquity, but also the maturing of art forms. Perhaps the true triumph of the Renaissance is its harmonisation of sacred and secular themes. Much of Renaissance art was inspired by – and financed by - powerful wealth-creating families and individuals.

Renaissance artists frequently expressed the authority of these influential personages through the use of religious themes and imagery. The most audacious of these works of art is Benozzo Gozzoli's "Journey of the Magi to Jerusalem" which is essentially a “who was who” of the court of Lorenzo the Magnificent, represented as the entourage of the Three Wise Men.

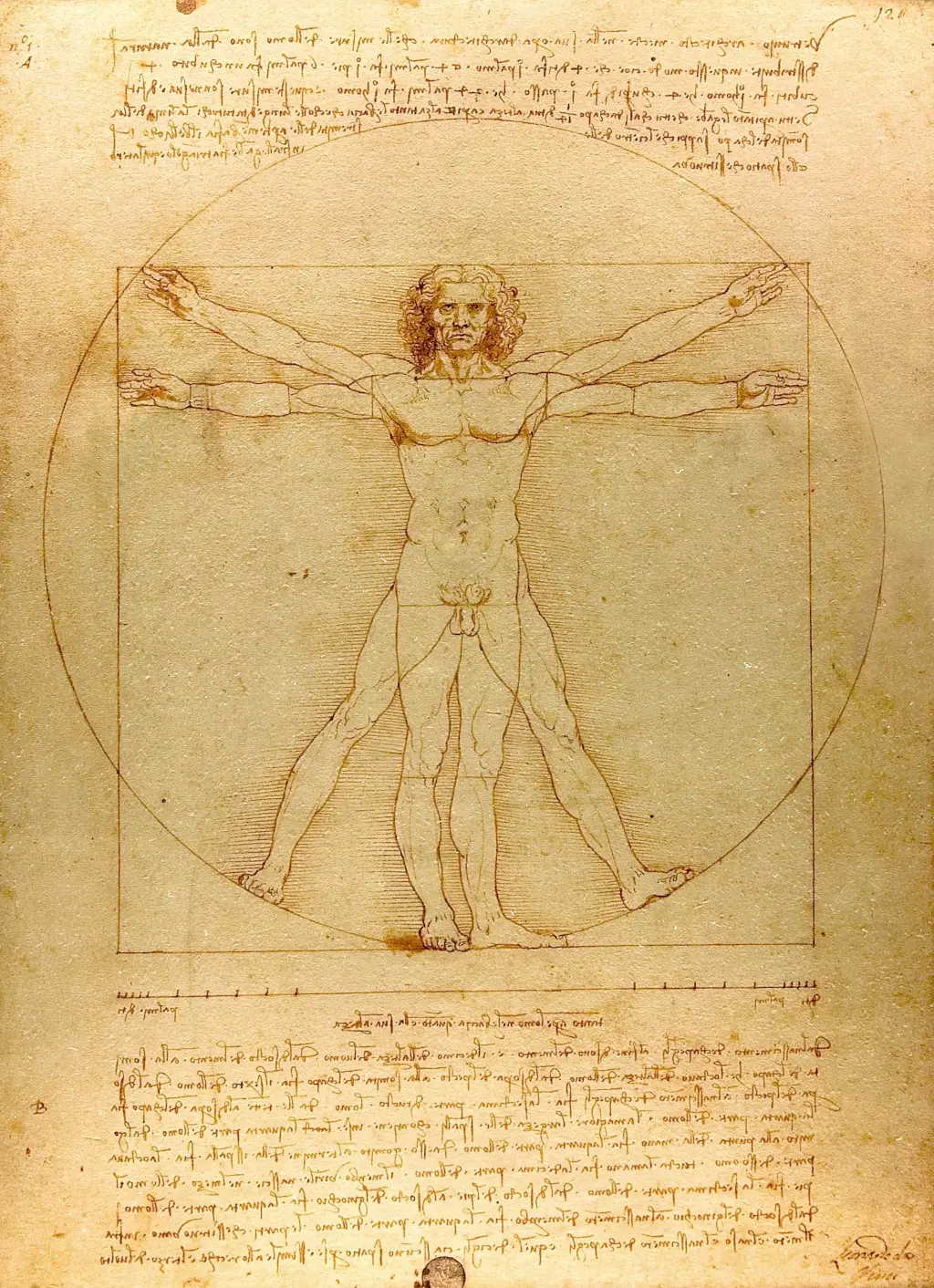

The Renaissance also marked the beginning of scientific thought, with the visionary works of Leonardo da Vinci and his experiments with anatomical drawing. Even as the Renaissance flourished, the seeds of religious and secular change were being planted, particularly in northern Europe.

The art of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries depicted powerful rulers and monarchs, displayed in rich settings and frequently on horseback. In the seventeenth century, secular rulers and soberly dressed merchants began to have their own portraiture as well, reflecting their increasing wealth and influence. See also the sculpture of Donatello.

Towards the Modern Era

After 1600, the history of art is one of increasing secularisation and specialisation. Portraiture of the aristocracy continued, as, for example, in the eighteenth century images of English Thoroughbred breeders and their horses. Different styles began to emerge, including more realistic scenes of everyday life and ordinary people, as well as idealised pastoral imagery.

European settlement in America and Australia brought new approaches and expansive themes, such as those of the Hudson River School. Art became a double-edged weapon; it could be used as a means of shared communication with other cultures yet could also be used for propaganda and imperialist ideology.

The increasing industrialisation of the nineteenth century brought greater dislocation and paradoxically greater freedom for artists. The idea of the artist creating his or her own vision without the need for a patron marked a major shift. Artists felt increasingly free to experiment, with the work of the Impressionists providing a leading example. Other schools, such as the Pre-Raphaelites, looked to the past, away from the ugliness of modern industrial production.

Modern and Postmodern Art

Rather than fearing or hating the modern world, modern artists embraced it. Long before John Brunner coined the phrase "shock-wave rider" to describe those who would have to adapt to the shock of emerging technologies, modern artists surfed the flood of new ideas.

Art was no longer about maintaining the establishment, but about the free exchange of emotions, thoughts and ideas. It was a means of personal and political expression. The separation of the establishment, and more importantly, religion, from art was viewed as liberating. Artists were now genuinely the avant-garde; they led the way to the new by example, knowing that change was essential.

Art became a revolutionary act, and while artists embraced the new, they did not worship its every aspect. Picasso's Guernica is rightly held up as one of the most significant works of the twentieth century: angry, moving and ultimately demanding a call to action. As post-modern artists continue to fashion their own personal and political responses to the world, they remind those who observe their work of the one common artistic thread through time: the vision of the artist.

Giotto.jpg)